What does one bag of beans mean in the global effort to end hunger? It turns out, a lot. 2016 is the International Year of Pulses. It is also the first full year in which we are officially working toward the Sustainable Development Goals, which set an ambitious but attainable target to end hunger by 2030.

An important part of this is improving the livelihoods of smallholder farmers – especially women. We have found a way of doing this that also strengthens resilience and improves nutrition: buying more beans and peas.

As the largest humanitarian agency fighting hunger worldwide, the World Food Programme (WFP) reaches an average of 80 million people each year with life-saving food assistance. We also work to eradicate the root causes of hunger; one way we do this is by sourcing our food in ways that build stronger and more inclusive food systems. In 2008, we launched Purchase for Progress (P4P) to explore how to source food more directly from the small-scale farmers. Purchasing earlier in the supply chain means a great deal of logistical challenges. To address these we have worked with a wide variety of partners, especially host governments and other United Nations agencies – such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) – to help farmers produce more, reduce their post-harvest losses and work together as businesses capable of dealing with everything from formal contracts to transportation. To date we have purchased over US$190 million worth of food from smallholder farmers, and have a goal to purchase 10 per cent of all our food within the next three years.

Supporting women farmers

These are all major steps toward forging more sustainable and inclusive food systems. But food systems must be inclusive not only of smallholder farmers in general, but women farmers in particular. Women farmers play a crucial role in agriculture – especially food production. But women’s labour is often invisible, unpaid and undervalued, and they usually have less access to productive assets than men. Plus, in many households, decisions about the production and marketing of crops are made by men. This leaves women providing a great deal of labour without reaping the rewards, and without the economic and social empowerment that comes with financial stability.

Our focus on supporting women farmers under P4P has taught us a great deal. We have helped women to access time and labour-saving equipment, such as cattle and mechanical shellers, to lighten their workload. We have also carried out awareness-raising efforts on the importance of gender equality, and held training to teach them to read and to increase their confidence. We have seen women’s participation in membership and leadership positions increase.

Our focus on supporting women farmers under P4P has taught us a great deal. We have helped women to access time and labour-saving equipment, such as cattle and mechanical shellers, to lighten their workload. We have also carried out awareness-raising efforts on the importance of gender equality, and held training to teach them to read and to increase their confidence. We have seen women’s participation in membership and leadership positions increase.

Despite progress made, we still face challenges ensuring that women are able to market the crops they produce. During the pilot implementation of P4P, it was discovered that one of the keys to unlocking women’s potential to participate in sales was a simple one: changing which crops we purchase.

Purchasing pulses

In many places, decisions about who produces and markets which crop are made based upon traditional gender roles. For example, in some parts of West Africa, maize and sorghum are considered “men’s crops”, while women produce pulses like cowpeas, beans and pigeon peas. Initially we were buying “men’s crops,” but we listened when women told us that they wanted a way of diversifying their incomes to provide additional benefits for their families. In West Africa, a local variety of cowpea called niébé is frequently produced by women farmers on small plots for household consumption. Niébé is difficult for smallholders to produce for sale – the seeds can be costly and storing them is challenging as they are prone to infestation. But with training from WFP and partners, farmers are now better able to produce niébé commercially. In some countries, women were provided with Purdue Improved Cowpea Storage (PICS) bags which are a cost-effective solution to reduce infestation in cowpeas. In Ghana, multiplication efforts have brought down the cost of seeds. Many benefits.

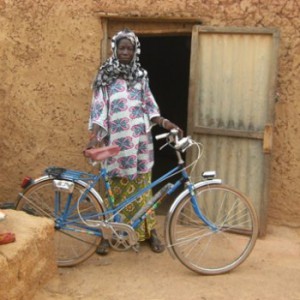

In Burkina Faso, 96% of participants in cowpea sales to WFP are women. Azeta Sawadogo is one of the farmers who have benefitted – achieving her lifelong dream to own a bicycle.

In Burkina Faso, 96% of participants in cowpea sales to WFP are women. Azeta Sawadogo is one of the farmers who have benefitted – achieving her lifelong dream to own a bicycle.

"I feel proud of myself and the group of women I work with in our decision to sell cowpeas to WFP. We are now admired in the village because even male heads of households do not own a bicycle."

In Zambia, almost half of the pulses used in school meals come from women farmers’ organizations. These women are looking beyond WFP to a variety of other buyers. With their increased incomes, they can invest in building new houses and sending their children to school. And pulses have many other benefits. Pulses are high in nutritional value – and in some cases, efforts to strengthen agricultural production of pulses have been coupled with nutrition-sensitive messaging – teaching farmers such as Awa Tessougué the importance of eating niébé at home for improved nutrition. Pulses are also resilient and environmentally friendly – they are generally drought-resistant and “fix” nitrogen in soil, meaning that they return the nutrients to the soil that can be stripped by the production of other crops. In building inclusive and effective food systems we must provide women with the tools to take part fully in decision-making processes. In doing so, we must listen to their needs and desires, and continue to learn better ways of supporting them to benefit from their agricultural work. There are many potential solutions to the challenges women face, and a great deal more work to be done. Purchasing more pulses may be only one of these solutions, but each bag of cowpeas is a good start.

By Edouard Nizeyimana

(Originally posted on www.farmingfirst.org)The original article can be found here.

Images copyright: Eliza Warren-Shriner and WFP